If you cut him open you’ll find only a husk. He looks like a person – more or less – on the outside, but that’s where the similarities end. There’s no need for him to make sure his insides match ours. No one will ever get close enough to find out.

He has rules to follow. He knows them the way that baby animals know their mamas right from birth. He can’t take anyone unless he makes a deal with someone. And he can only take the person they love most as payment.

The first time she heard about the Salesman, Grace was playing in the creek with some local kids. She’d only been seven, but that’s the way it was in their town; you turned out the kids in the summer and let them loose as soon as they were old enough to walk.

The townsfolk didn’t much like Grace by the time she hit double digits. Her daddy went away for shooting her mama when she was just ten. Somehow this was always Grace’s sin, especially now that her grandma isn’t around no more to be blamed for raising her son wrong. Grace has never cared all that much for the townsfolk neither. They never liked her family. Called her grandma crazy after Grace’s granddaddy left his wife and son decades ago. Grandma swore that the Salesman had taken him up until she died. Townsfolk looked the other way when Grandma and Grace walked through town as if they hadn’t been telling stories about the Salesman only moments before.

He can cure anythin’. Everythin’.

The embarrassment of being told by the townsfolk that her Grandma had lost her mind was that much worse because Grace could tell, too. Grace knows why the townsfolk called Grandma crazy, even if they were just as superstitious as she was. Sure, she heard lots of rumors from the other kids, but most of the rumors came from Grandma. She told Grace that when the Salesman was coming, she’d know because the wind would blow the wrong way, and the animals would go stir-crazy.

Grandma kept the gun by the front door and spent most of her time sitting on the porch once she got too frail for the farm work, watching the road for the return of the Salesman. Grandma made her practice with it on the weekends, and after she’d shattered all the bottles, Grace would wash her hands in scalding water until the skin was an angry red.

“How can you keep that gun in the house after what Daddy used it for?”

“He’ll come back Grace,” Grandma told her, and she knew Grandma didn’t mean her Daddy. “I know he will. I’ll be waiting.”

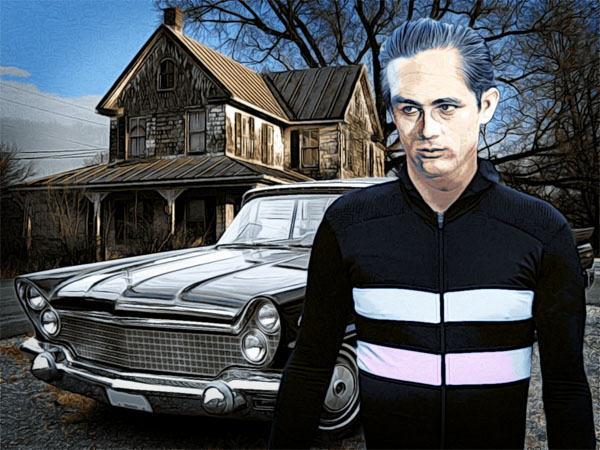

He looks fine as James Dean. Used to turn the heads of housewives all over the state back in the ‘60s. That’s when he first showed up in his Lincoln Continental, his car nicer than anyone in this town’s ever owned. He’s got that slicked-back greaser hair but he wears it more grown-up-like. His teeth are paper-white and if you don’t look too close, they’re just as blunt as anyone else’s.

He doesn’t age. You’d know him right away because he’s worn the same skinsuit over his husk body for forty-some years.

No one knows where he goes when he drives past the tree line. They just hope he won’t come back outta it again.

After her daddy got taken away to jail, Grandma told Grace about his dreams. When he was a kid he was plagued by nightmares. Awful, awful dreams. Night terrors.

“That’s how the Salesman got him,” Grandma told her. The Salesman came by one afternoon when Granddaddy was out in the fields and Grandma was in the kitchen pouring lemonade from a pitcher ‘cause it was dreadfully hot.

“I told him to get the door. I was in the kitchen. I didn’t see what happened.” Grandma couldn’t look at Grace when she told her this. Her eyes narrowed, staring off over Grace’s shoulder as if remembering something distant. “I was lookin’ out the window. The animals were running amok and your Granddaddy was just starin’ up at the trees, doing nothin’. Just starin’ up at the trees.”

“I don’t understand, Grandma.”

“I went out the kitchen door, and then I looked at the trees, too. The leaves were blowin’ the wrong way. I could feel the wind, and it wasn’t blowin’ the way the weathervane said it was. And the bleatin’ of the goats. I couldn’t hear anythin’ over it.”

Grandma told Grace that she never even saw the Salesman. By the time the wind had died down and the animals had quieted, Grace’s daddy had come back into the house with a strange bottle he swore up and down would stop his night terrors.

“I didn’t know,” Grandma said to Grace, a tear slipping out past her swollen lid. “I couldn’t have known.”

A day later Granddaddy was gone.

“It’s just like they say,” Grandma whispered to her. “He takes the one you care about most. That’s the price you pay.”

Her daddy had been the same age as she was when she lost her mama. Grace never had the heart to tell Grandma that Granddaddy just abandoned them, not after she admitted she thought her son loved him more, but her Grandma must have known what she thought.

If you open the door for him, it’s already too late. He’s got magic in his voice. You’ll buy anythin’ from him, for any price. There’s no way outta that.

Grace and Grandma fought all through Grace’s adolescence. Grace blamed her daddy for no one ever talking to her at school. She blamed Granddaddy for ruining their family long before Grace was even a thought in her mama’s head.

“You can’t blame your Pa, it wasn’t his fault any more than what happened to your mother was your daddy’s fault,” Grandma said. Grace was only thirteen. The wound was still so fresh. “The Salesman came back. I felt it in the air and this time I was almost ready, but your daddy got the shotgun first. Your mama was making a deal. He did what he had to do to protect you. Your mama loved you more than anything. Your daddy does too.”

Grace screamed, then, shouted at her Grandma that the townsfolk were right, that she was crazy.

But aside from Grandma, Grace was alone. She met boys at high school and smoked with them and kissed them in the backs of their cars in empty parking lots, but she never cared for them. Eventually, she stopped bothering with other people altogether.

Grandma died during the dog days of summer when the drone of the flies is at its worst. Hearing her son passed away in prison pushed her frail heart over the edge. She leaves Grace with the responsibility of selling off the animals one by one before she can sell the farmhouse, too, and wipe her hands of it all.

Grace has just sold off their best dairy cow when she feels the gooseflesh invade her arms. A sheep somewhere behind her bleats, and a goat follows suit. The windchimes blow and the leaves bend backward the way they do before a big storm, except the wind isn’t blowing that way. The bleating gets louder. She hears the stamp of hooves like the four horses of the apocalypse, but she knows it’s just the farm animals.

There’s just something so familiar about it all, that even once she’s inside the kitchen, she can’t shake the chill of the wind. It’s awfully cold for the end of September.

I can’t remember the last time someone’s knocked on that door, is what Grace thinks when she hears it happen, echoing through the empty house loud as a church bell. She still doesn’t believe – she swears to herself she will never believe, never go crazy in this house like Daddy and Grandma – but her hand shakes when she turns the knob and opens the front door. The warnings never stuck, she supposes.

Behind him is the car, but otherwise his form overwhelms the doorway. It looks just like they said it would. Something out of a vintage car mag, shiny as a brass button and black as the jet of his slicked hair. His eyes are the same oppressive blue of the summer sky, and just as heavy on her face. And he is handsome, the kind that makes women grab their pearls and men get all red in the face. If you don’t look too closely. If you do, you see his skin is pulled just too tight, the desiccated form underneath peaking through at the corners of his eyes, under his fingernails.

“What can I do for you?” Grace asks because that’s how Grandma raised her, to have manners.

“The real question is what can I do for you? What is your woe? Your ailment? Truly, I have anything and everything to help.” His briefcase is the same matte black as his fine pin-stripe suit. He opens it just wide enough for her to see the secrets that lay inside, the potions and oils that would fix anythin’ and everythin’. When he speaks his words hiss out his teeth like he hasn’t gotten saliva quite right, and even in his dark suit, he hasn’t broken a sweat as if he can’t do that like other humans either.

“Anything?” Grace asks. “You can do anything?”

He looks down his perfectly straight nose at her. “For a price, of course.” She feels the magic the kids always spoke of trying to breach her skull, but it can’t. It won’t.

“Naturally,” Grace agrees. Her hand creeps to the door jam, and then just a little further right. “You see, unfortunately, I can’t make a deal with you.”

“And why is that?”

Her fingers find the barrel of the loaded shotgun that Grandma insisted always be right inside the door, and she levels the barrel at his chest. “There’s no one left for you to take from me.”

She pulls the trigger before she can think this might be a mistake and falls backward from the kickback. The Salesman looks down irritably at the hole in his chest. There is no blood. There is no anything. Just like they said there wouldn’t be.

He backs away slowly, closing his briefcase, and then all at once he runs to his car. Grace is still as a stone for the second it takes for him to pull out of the farm’s drive and start down the long, straight road to the tree line.

Then she’s in motion, pumping the barrel of the shotgun and letting the spent shell fall away. Now, the shotgun is riding in the bed of the truck, and she starts the engine, and it’s the loudest sound she’s ever heard.

He may have a headstart, but his car isn’t built for speed. They’ve passed into the tree line by the time they are almost bumper to bumper. The Salesman turns around to face her in his car and hisses, his face ripping open at the seams.

Grace’s truck hits the back of his shiny car, which, for the first time in years, looks slightly less than brand new. The tires falter but don’t fail. So Grace stops the truck and gets out, grabbing Grandma’s gun and leveling the barrel as best she can at his retreating car. She pulls the trigger again. She misses him, but not so terribly, because she’s hit his back wheel. The car turns to the right into the trees, and Grace knows there is no road there. But by the time she has run to where the skidmarks in the road veer off, there is nothing to be found.

Where has he gone?

It takes a long time for Grace to feel safe letting herself care for someone, but, eventually, she does. She still keeps a shotgun in her new home. Just in case. And she never goes back to the farmhouse.

Years later, a hunting party is sure they’ve found a body, a human body, but no, they must be mistaken. It’s just a husk.