Consider this letter your inheritance.

I, Joseph Matthew McDormand, do hereby bequeath to my daughter, Erin Kathleen McDormand-Donato, all my worldly possessions, which can probably fit into four or five shoeboxes.

And I also bequeath this, my testament.

My confession.

I couldn’t save your brother, Baby Benji, but I can help people who’d been mistreated by corporations. And that’s what I do, Erin. I didn’t have much when I went on disability because of my damaged liver, but I did have a computer, one that I’d built myself. It had been easy for me to go to the darkest corners of the dark web to find the “tools” needed to hack into corporate HR files. That’s where I find the stories. That’s where I find the victims of corporate callousness.

I write to tell you what I’ve been up to for the last four years. I’m pretty sure you’ll get this even as the FBI circles. I am betting that they’d have no reason to intercept this letter since they’re so focused on connecting the dots of an email maze that I thought they’d never be able to follow.

But they did follow it (with a little help).

Agents will be banging on my door within a few days. I will not answer because I will have killed myself by then. You’ll get this at about the same time, Erin. When the landlord lets the FBI in, there I’ll be. On the pullout couch. A casualty of an overdose of downers. Reposed with rosary entangled in fingers that rest on an open Bible, with John 1:5 circled: “And the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness comprehendeth it not.”

That’s just how I would like to be laid out for my funeral, except I want to be cremated. Please take note. Near the box with my ashes display the photo from my young adulthood when I dreamed of being the next great Irish tenor, right up there with John McCormack or Frank Patterson or Ronan Tynan. You know the one: My publicity shot: “Jimmy McNear, the Irish Balladeer.” You used to goad me sometimes about my stage name.

You’d say: “What’s so different? Joe McDormand? Jimmy McNear? I could see if you called yourself Giuseppe Victorino, or something.”

At a certain point I’d stop debating you, Erin, because you always won. You’re your mother’s daughter (and thank God for that!). That’s why this posthumous letter. If I told you my intention by phone or face-to-face you’d talk me out of it.

But how did I get here? To this moment? To these, my last moments?

It works this way.

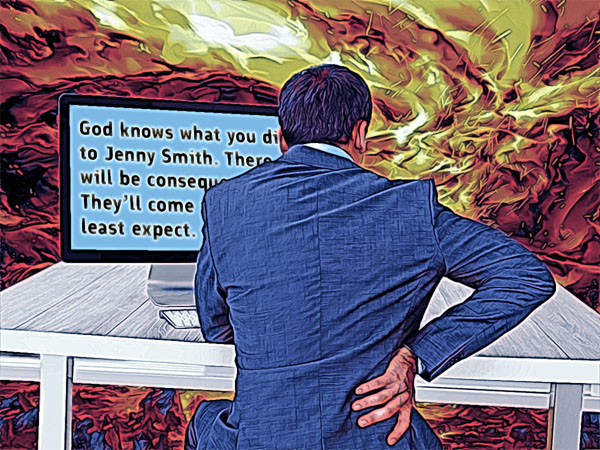

I write vitriolic letters to those who’ve mistreated their employees; those who’ve turned them into former employees. Threatening messages. Like: “You are going to die within the next nine days. A painful death and you won’t see it coming.” I get into more personal details on a case-by-case basis. These make the threats even more alarming. I’d use the names of the their loved ones; spouses and children.

Don’t judge. These corporate types deserve it, and I have killed no one, Erin. I have injured no one. I do weaponize words. That I do. I hold a mirror up and say: “This is what you are. God knows what you did to NAME OF VICTIM HERE. There will be consequences. They’ll come when you least expect.” What I mean is that God will judge them. God will stand aside as they die painfully. But so what if these soulless lowlifes worry about a comeuppance from somebody in this world? I cannot control how my messages are interpreted.

Of course, the authorities immediately contact the former employees who know nothing about what I’ve done. They’re interrogated. The agents seize computers, cell phones, files and anything else that the former employees might have.

Usually the victims offer DNA, submit to a lie detector test, cooperate in every way. They’ll swear they’re innocent and they will eventually — sooner rather than later — be found blameless because they really are innocent. They don’t know who might be using their name in the terroristic threats emailed to the people who’ve either ruined their lives, or couldn’t care less if they ruined their lives. Some of them might think — but never dare say aloud — that though they had nothing to do with the threats, they can’t pretend to feel sorry for their former toxic bosses.

I thought I could get away with it because what had happened to me, how a corporation screwed me over, occurred years ago. The hardest crimes to solve are the ones without motive, or motive buried deep within the muck of personal history. You know my story all too well, Erin, but I’ll tell it again just in case this letter gets confiscated or becomes evidence in a trial that should never happen since the prime suspect (that would be me) lives no more.

Remember? My company wanted a complete overhaul of their tech system.

The installation of new platforms for human resources, new training modules for recent hires, and just … the works. I dove in, doing the job of three people but apparently not fast enough so they hired an outside vendor to help.

“It’s a lot to ask, Joe,” my supervisor sympathized. “We realize that.”

He’d risen to be the vice president of production and cultivated a demeanor and voice that made you feel that of all the people in the world, he’s so overjoyed to be talking things out with you.

“Thank you for understanding,” I said.

I’ve encountered such “friendly” bosses before and should have known better. In this guy’s case, though, we’d shared a few beers after work sometimes. We bonded. So I thought. But he noticed.

“Don’t you think you’ve had enough, Joe?”

“One more for the road!” I’d exclaim.

Oh yeah, the drinking.

I did begin drinking at one point in my journey, and I mean really drinking, because even though I drank before — and often too much, especially on weekends — this was something else, a new stage. Joe McDormand dives into the void. About 10 years after Baby Benji, it started. You remember, Erin.

You and your friends driving around our town saw some drunk stagger into a bar.

“Yeah, that’s just what you need, dude, another beer,” one of your friends said. So you told me much later.

All the girls laughed as did you, but you hoped that your companions didn’t realized on that cold and brittle February night that you faked your laugh. Because I was the disgustingly drunk man stumbling from bar to bar. I came home so many nights stinking of beer, whiskey, alcohol, and piss.

You must have told your mother about that incident. You didn’t want to, but she dragged it out of you the way your mother does. That was it. The end. I had shamed our child — our treasure — one too many times. She kicked me out the next day.

My struggles worsened after I left. (No surprise there.) Spotty employment. I drove a cab for a bit. Lost the cabbie job when I got my license suspended and then, finally, revoked altogether. Guess why? Other odd jobs here and there. Lived in boarding houses, and went to “where the ragged people go/Looking for the places only they would know,” as the song says. Medicaid, disability, food stamps. Limbo. You’re all too familiar with this story, Erin. You’ve heard too many variations of it from patients because that’s what you do: You help people in crisis.

Erin McDormand-Donato — Psychologist.

Seven years, three months, two weeks, and four days ago as I write I awoke one morning full of disgusting self-pity and stumbled to an AA meeting held in the basement of Saint Brigit’s Church.

My name is Joe and I am an alcoholic.

I never told you or anybody else that Baby Benji appeared to me the night before. It may have been delirium tremens, it may have been a dream. It may have been an overstimulated subconscious. Or, it really may have been him. His soul. One of the Holy Innocents. He said “Da-Da” raising his hands the way he did when he wanted me to pick him up. I stooped and grabbed him under the armpits but couldn’t lift him. I strained as he kept saying “Da-Da” more and more insistently and the phrase became a cry and I awoke gasping, thrashing.

I lay there weeping about my wasted existence.

I finally got out of bed and there on the nightstand rested an index card. Scrawled on the back, the side without lines, in black magic marker: “NEW LIFE.” Did I write that? I must have, though I never did find a magic marker in that room. Giving myself one more chance to not quite make it. Except this time, I did.

I. Did.

I loaded all the beer and liquor in my room into a box and pushed it out into the hallway where my fellow boarders would take what they needed. When I next opened the door, the box was gone. I marched over to the basement in Saint Brigit’s Church at noon. High noon. That’s when they hold their AA meetings. Saint Brigit, the patron saint of beer. I don’t know what to make of that, Erin. You’re the psychologist. Maybe you can figure it out someday between finishing the New York Times crossword puzzle and jetting off to one of your conferences.

When I got sober, you told me how proud that made you. You told me that you forgave me. I wasn’t an abusive alcoholic. I was a slushy and blubbering alchy. Disengaged. Floating. A ne’er-do-well. You forgave me for being weak. So many parents lose a child and don’t go to pieces.

You were right. Getting fired and mistreated by corporations didn’t help, but the line connecting cause to effect can stretch over years. What happened to Baby Benji: That’s why I guttered.

My beautiful Baby Benji — normal and talking until the age of three, full of smiles and promise — until the spinal meningitis. I remember sitting you down — seven-year-old you — and “explaining” that the angels came and took Baby Benji away.

Now, getting back to getting fired. Here’s how it happened to me.

I was so thankful that my boss realized how much I struggled with the systems overhaul and sent in reinforcements. The young woman who came to help me could do anything — incredibly competent — and was one of the most pleasant people I’d ever worked with. Finally, when things looked like they were up and running, I took a long-overdue vacation. That’s when they fired me and hired that young woman. I had been training my replacement.

That’s the way corporate America rewards loyalty and hard work.

The bastards shouldn’t be able to get away with it. I investigated suing them but the lawyer said that in at-will employment states — that is, almost all states — employers can fire somebody for any reason or for no reason at all. Which, of course, fuels capricious brutality.

Justice. I craved it.

I never retaliated against that vice president, not with my computer background and plenty of motive. Was I drunk or sober when I came up with the idea of seeking revenge for other workers who’d been screwed over? By that time, sadly, the two states of being — drunk and sober — existed side by side, with slight hangovers bridging the gap.

Being a drunk’s a full-time job.

Then, the epiphany — the visit by Baby Benji — and I got sober. I still raged within, though, thirsting for vengeance. I know that this is the wrong path. Forgive your enemies, right? Hell, love your enemies. Well, Jesus and the saints might be able to get there but the rest of us struggle. Sometimes, I can barely love the people who love me. Except for you, Erin. Except for you.

But you deal with this all the time, don’t you? Anger is common in recovery. I needed to channel mine. So, I became this emotional Robin Hood. I’d write the emails to the miscreants who so blithely screw people over. It was binary. Good versus evil. I was good. They were evil.

Except that it’s way more complicated than that, isn’t it? Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago: “If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

Who indeed?

My emailed threats amount to messages in bottles being thrown into the boundless ocean. I cover my tracks. I do not make the mistake of the arsonist who stands with the crowd watching flames engulf the object of his desire. Or the murderer who cannot resist returning to the scene of his artistry. I let it go. I don’t follow up. I don’t search for names of either the victims of corporate soullessness, nor the perpetrators of the “it’s just business” mentality. I leave no clues.

Why would I do as an arsonist or murderer does? They are evil. I am not.

Right?

Solzhenitsyn again: “In the intoxication of youthful successes I had felt myself to be infallible, and I was therefore cruel. In the surfeit of power I was a murderer, and an oppressor. In my most evil moments I was convinced that I was doing good, and I was well supplied with systematic arguments.”

Why the Solzhenitsyn quotes? Well, Erin, many people quote the writer, or allude to his hard-won wisdom. For me it’s one prisoner talking to another. He, a prisoner of the gulags. Me, a prison of addiction. A specious comparison, I know. There’s a real difference between a government abusing you and you abusing yourself. But such metaphors have to do.

Specifically, I turned to Solzhenitsyn after happening upon an article about my former boss, the vice president who’d so cavalierly tossed me aside.

The headline:

Hospital Wing Arises From Businessperson’s Grief

You can find the article easily enough on the web, Erin. I never told you his name, because one of the steps in dehumanizing entails erasing the name. It’s Gleeson. Ben Gleeson. The grubby little middle manager had risen to be a player, a man of consequence in this world. Started his own company. Made a fortune.

No one escapes life, though. No one escapes the pain that existing entails (nor the beauty, I must quickly add). Turns out that the hospital wing Gleeson finances will focus on battling spinal meningitis. A few years after I’d been kicked to the curb, Gleeson married and began a family. God or fate or Darwin had other plans. His first child, a baby girl, died of the disease when she was about a month and a half old.

From the article:

“‘I’ve done things in my life that I am not so proud of, sure,’ Gleeson said. ‘I was driven and if someone wasn’t a good fit, I cut them loose. I think anybody who’s ever managed anybody can identify. That said, I wish I’d been better to people.’ He quickly added: ‘I don’t think that God is punishing me. No. I don’t believe in that sort of God. But what happened to my Nora made me examine my life and made me realize that I need to do more good in this world. There’s a beautiful angel looking down on me now. Watching Daddy.’”

I didn’t know it then but a plan hatched that day. The plan leading to this letter, Erin. I rummaged through the minefield of my toxic history. Had I ever wished for Ben Gleeson to have something happen to him like what happened to me with Baby Benji? I always said that I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy and for a long, long while that had been Gleeson.

Answer: I don’t know. The thoughts of a substance abuser are difficult to trace.

Then I read Gleeson’s obituary. That came about four months after the article about his bequest. It said he died “suddenly.” I knew what that meant. Unlike Richard Cory (Google it), it’s no mystery why Gleeson took his life.

In dreams Baby Benji looks at me with eyes too full of disappointment. These horrible, horrible dreams. I recalled how many mornings I’d awake after my child’s death thinking that I didn’t want to go on anymore.

Do I regret sending the terroristic threats to the ones who’d unjustly fired their employees? The answer is still “no,” but it’s now a qualified “no.” They did ruin lives. I still believe that seeking some sort of justice on behalf of the bullied and betrayed puts me in the right. Though, now, I am not quite as sure. Solzhenitsyn said that “even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains … an unuprooted small corner of evil.”

I could have continued for another few years, perhaps indefinitely. The FBI didn’t crack this case. I purposely helped them. My ending can be seen as a slow-motion suicide-by-cop.

That is my story, Erin. That’s my confession. I have nothing left. In the no-man’s land of my history there sprout some flowers. One is your happiness. You have a wonderful husband and a great life. Cherish them. Be as strong in the face of tragedy — which eventually hunts down every human being — as I was weak. Be as mindful of the many blessings you’ve been given as I was oblivious. We’re alike in many ways but so different in others. It’s that difference that will sustain you.

I do miss that I won’t be here to see my grandchild. You can’t tell me that that’s not next on your to-do list. I would love that baby so much. If there’s a heaven and I somehow make the cut — and the God I believe in is a God of love and forgiveness; I suppose Gleeson and I are more similar that I thought — I would be that baby’s guardian angel. When the baby grows up, Erin, and starts asking questions about me, be honest. Give all sides of the argument. All sides. Show this letter if you decide not to burn it.

And if you can, remember me at my best. Once in a while pull out that family photo of me, your mother, you, and Baby Benji, that was taken when he was a healthy, growing toddler, and life overflowed with hope and joy. Those were my happiest years.

Know this, Erin, my child. I love you. You are still my treasure. Please tell your mother that I love her as well and that I deeply regret putting her through all that I put her through.

And now, go in peace.