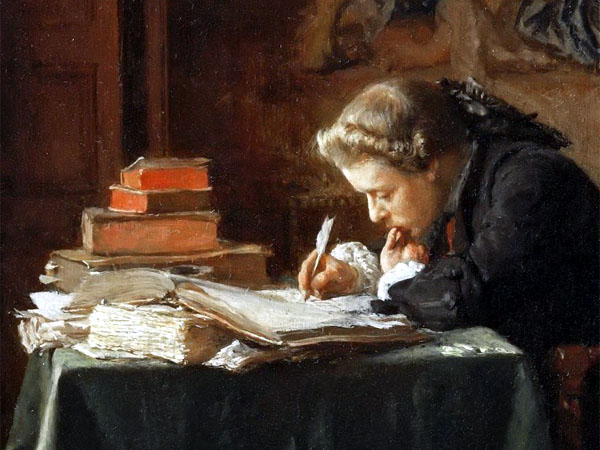

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, “Young Man Writing” (1852)

I still remember sitting down in a Sydney city cafe, sometime in the afternoon, and writing the first chapter of what was going to be my next novel. I had some prior outlines and plot sketches, but November 8, 2016 was the day I started putting pen to paper. I kept plugging away at it until, in May 2017, I had a first draft.

In 2018, “Gollancz,” the science-fiction and fantasy imprint under Orion Publishing, announced that they’d be buying “Stormblood” as the first book in a contracted trilogy, for a planned release in hardback and trade paperback in February 2020. And, like any other traditional published book, it goes through the rounds of editing. I’d already edited the book thoroughly, with myself, beta readers, my agent. When it ended up in the hands of my editor Gillian Redfearn (who also edits Alastair Reynolds, Joe Abercrombie and Richard K. Morgan) I thought there wouldn’t be too much more work to do.

I was very, very wrong.

There’s a lot in this industry that isn’t always transparent but should be. Many of you may be interested in working with a Big Five editor yourselves one day, so I wanted to provide some insight into the guts and gears of the editing process, the various hoops and cycles a book goes through, and what my personal experience has been in crunching the revisions.

I believe it’s very underestimated how extensive the editing process is when it comes to traditional publishing. We’re not talking about cleaning up typos, chopping away gratuitous sentences and chapters, or even tweaking character arcs. No, we’re talking about digging down into the root canals of the narrative, the bones of what gives a book its identity. Fleshing out the ambiance, the structure, the voice, the style, and using this understanding in context to influence how you approach edits.

It sounds like a mouthful, but it’s necessary to see your work from a different light. And it’s necessary to take that mental stance when editing. It’s so easy to get caught up in the minute, in one chapter, that you don’t take the necessary steps back and look at the book as a whole. That scene has great dialogue, but is it disrupting the pacing? That’s an interesting turn of events, but could it be entirely rewritten to be better? The tricky thing is, it’s not about what’s objectively better. It’s about whether it’s better for your book, your style, your voice. If I wanted to have my book have breakneck pacing from cover to cover, we’d be taking a completely different approach.

So that’s what we did for the first round of edits. In taking a step back and looking at the naked scaffolding of the structure, we realised there needed to be some changes early in the book, in terms of character motivation, relationships and backstory. Which changes the way the entire book, and the main character, comes across. Not in a major way, but significantly enough. And that’s where playing word jenga comes in: because the wrong sentence in the wrong place can get your entire book to come crashing down around your head.

None of this was forced upon me, though. All editorial was a conversation from start to finish. My editor didn’t tell me to make structural changes or rewire entire characters: she made suggestions and encouragements to consider the benefits of doing it, and what the end result would be. I’m the one who made the decision. It was never out of my hands.

After we agreed to make the change, my editor worked on the first half of the book to reflect this. This meant tweaking characters, shuffling certain flashback scenes. At this point, I don’t touch anything on a sentence-level, any of the prose. This is all big-picture stuff.

I applied the changes, and sent it back to my editor. My editor then re-edited the first-half of the book again, because she’s a pro, and edited the second half in as a consequence of the changes we made in the first half. Because, if she didn’t, we’d be seeing two very different stories. This is what I meant at the start, about looking at the bare bones of your book.

So I edited the second half again. Tightening characters, adding and removing world-building, checking for continuity, and in some cases, completely re-writing scenes, or the internal mechanics of a scene. This means I change what the characters go about doing in order to complete their goals, whether they accomplish them, what the consequences are. Big-picture stuff that ripples out. As an example, one battle sequence was very run and gun. We retooled it to be about tactics and team co-operation. Another scene had a character try to get information from someone, blowing his cover pretty soon and searching the guy’s place. Instead, I had him remain undercover almost the entire time, slowly up the dread and tension the two characters play verbal cat and mouse, until one breaks.

It’s a hell of a headache, and it’s not easy to take scenes that have written a certain way, been in place, for years, and strip them out and completely retool them, but it’s necessary. And it almost always means a better book.

Then comes my next pass. I make most use of my editor’s comments in this round. Plugging logic gaps, tightening sentences, adding or deleting sentences, making sure all the dialogue is consistent with the characters, chopping away the ugly word clay, fixing up the location of the scene (and moving it, if need be) making adjustments that impact the scene, but nothing else. This is where the book is more or less falling into place. It’s probably the part I enjoy the most, putting the meat on the bone so the plot, story, characters and descriptions read smoothly and consistently.

The next round is where I am now. Fixing up sentence-level structure, word-choice, prose, and descriptions. My editor’s mighty red pen has left it’s mark on every single page, so there’s no getting away from it. It’s tempting to call it purely cosmetics, but my work is first-person, very voice-driven, and the state of the main character absolutely impacts the prose. I don’t care too much about flowery word-choice or elegant descriptions, but I absolutely care about each word sounding like it could come from the protagonist’s mouth. So I make sure my sentences are running smoothly, so a heedlessly complicated word or turn of phrase doesn’t turn into a jolting speed-bump. I ensure the sentences and paragraphs have a nice rhythm and balance to them. I deliberately purge any “flowery” prose, any words that detract from the tone I’m trying to strike, any poorly-timed metaphors. So words like “illuminate” and “sparkle” or any of their relations are chopped out. I’m trying to write sharp, razor-edged prose with a good dose of sarcasm and cynicism when needed. So specific word-choice, and how the words are conveyed, matter.

And then, of course, when all’s said and done, there’s copy edits. So there’s a lot of hours and a lot of work poured into editing a book, both by the editor and author. But here’s the thing about print: it lasts forever. So if a sentence, paragraph, chapter, or even character, is lacking, it’ll be lacking forever. And it’s my debut, and you know what they say about getting one chance to make a first impression.